Trump Tariffs and Industrialization: Has Import Substitution Worked?

Or, Everything Old is New Again.

Welcome to Economics, Frankly.

I intend to write here occasionally on, well, economics and economics-adjacent topics. Time permitting, I hope to have longer posts writing along the lines of my Noahpinion post, but to keep things going, for now, I want to do some shorter posts.

Given the extraordinary tariffs that Trump has just put up and some of the stated rationale behind them being the idea of helping the US to industrialize again, I thought a small discussion of the experience of Brazil and Import Substitution (IS) would be useful to illustrate the pitfalls of these types of policies.

Import Substitution: the Basics

What is Import Substitution? As the name suggests, the idea that a country can stop importing certain types of goods and, instead, have them be produced domestically. The main method for achieving this is remarkably simple: set import tariffs high enough and the cost of imported goods will skyrocket, meaning that domestic and foreign producers will want to create factories to produce said goods domestically instead.

Note something important here: the goal isn’t to create export industries, but industries that will furnish the domestic market. This will be an important element for the discussion up ahead.

Although the primary method associated with IS are tariffs and similar ways to restrict imports, such as quotas, other tools are commonly used too. In the case of Brazil, import tariffs for capital goods (that is, machines, robots, stuff used to make other stuff) were lowered to help promote import of those types of goods, and federal spending was deployed directly and indirectly as we’ll see.

As a side note, the intellectual underpinnings for IS seem to come from much earlier, but as a “fad” that swept Latin America in the 1950s, a lot of the basic idea behind it came from Dependence Theory. This theory essentially states that international trade would permanently keep poor countries poor and rich countries rich, by forcing poor countries to specialise in goods that would never improve in the terms of trade; i.e., poor countries would solely export commodities (whose value goes down over time) and rich countries industrial goods (the opposite). Somewhat ironic given the current status quo of not-yet-rich China.

Brazil and Import Substitution, a Promising Start?

When did Brazil begin its IS policies? The common start date I think is sometime during the Vargas dictatorship of the 1930s. But I want to focus on later efforts, so I’ll briefly summarise the existent industry and IS policies pre-1950s. Brazil had a small, but significant industrial base focused mostly on São Paulo and other areas with immigrants before the 1930s, although it can probably described as a somewhat “primitive” industrial base. Brazil at that point was mostly a agricultural country, with coffee being its most important product.

When the Milk coffee politics ruptured in the late 20s and Vargas quasi-fascist dictatorship took over, the policies Vargas pursued led to significant more industrialisation. These policies were mostly focused on reducing imports1 and so, arguably, do qualify as a version of IS. This, plus a boom stemming from WWII meant that Brazil had a surprisingly large industrial base before “classic” IS policies really took off in the 1950s:

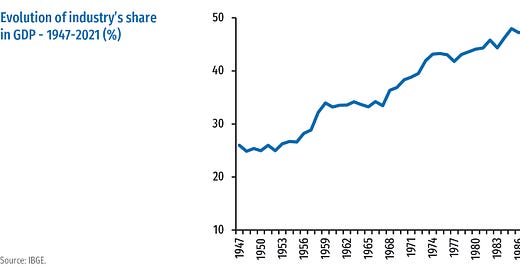

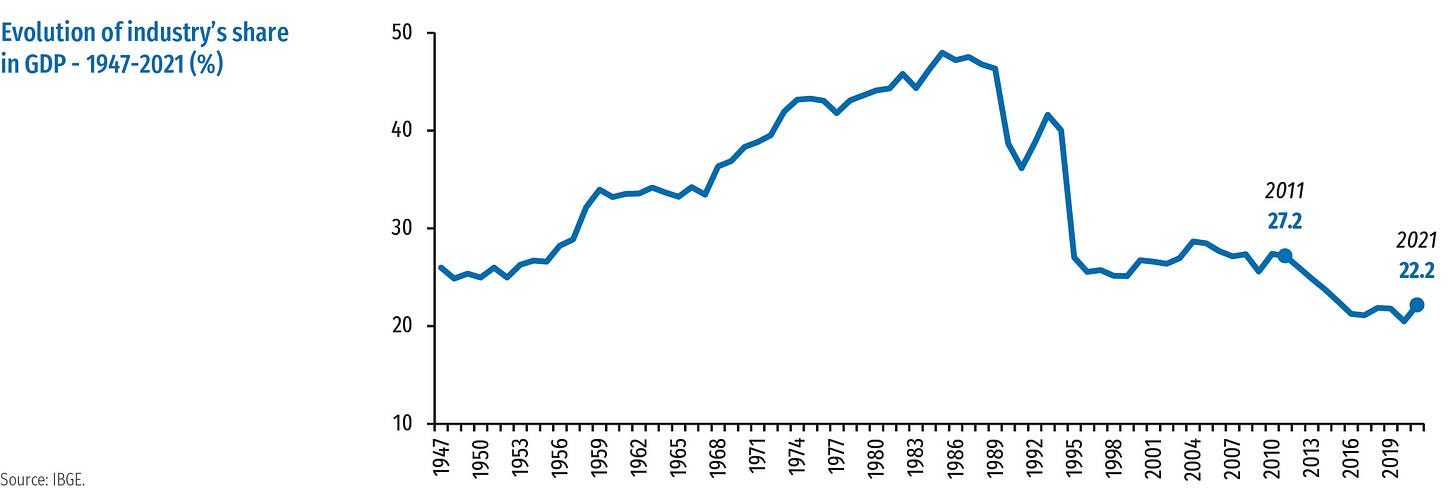

Source: CNI, https://www.portaldaindustria.com.br/estatisticas/industry-in-figures/

Still, as the graph above shows, Brazil hadn’t fully “industrialised” by this point, and it would be the “classic” IS policies of the 50s onwards that created the big boom in industrialisation that last from the 1950s to the late 70s and early 80s.

What were the IS policies of the 50s? Tariffs played an important element overall and sometimes reached as high as 150% for some types of industrial goods2. De-facto quotas via import licenses were extensively used to achieve a similar effect.

This wasn’t the end-all, though, several other policies were implemented at the same time. Capital goods3 for industry were given special exemptions as imports. Government spending came to fore in different ways: indirectly via state bank lending to favoured companies and by setting up state companies in key areas4 and directly via infrastructure development (including the expensive development of Brasilia), although the latter wasn’t totally confined to pure IS policies.

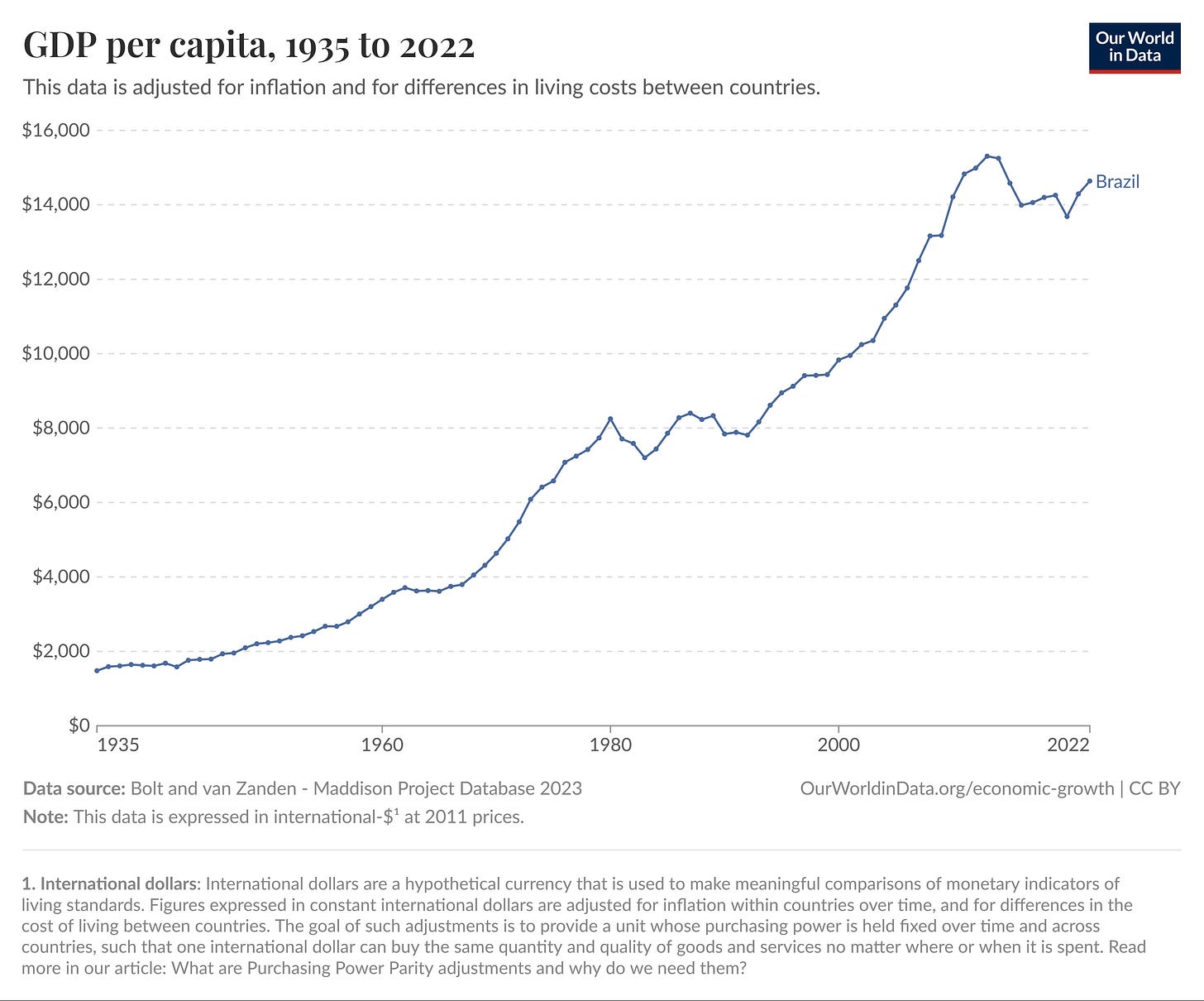

For a while, things looked pretty good and the relative continuity of these policies encouraged significant amount of FDI and overall growth. There was also an attempt to boost industrial exports to diversify exports away from purely just commodities for a few years. Brazil’s growth in GDP per capita had a significant increase and Brazil went from being a poor country with GDP per capita of around $2000 in 1950 to a middle-income country with GDP per capita of around $8000 by the late 70s.5

Source: Our World in Data https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/gdp-per-capita-maddison-project-database?tab=line&time=1935..latest&country=~BRA

Import Substitution’s End

So far, so good! But, as the graphs above already show, the good times most definitely did not last. The oil shocks of the 1970s led to a huge problem for Brazil, as the cost of imports of oil skyrocketed and all these “shiny” new industries were not exporting nearly enough to pay for these imports. The dictatorship faced then essentially two choices: either they could severely restrict imports of oil, which would mean lowering growth for several years as oil was not replaceable in the short run, or they could double down, borrow a lot of foreign debt to keep imports high and sustain growth for longer.

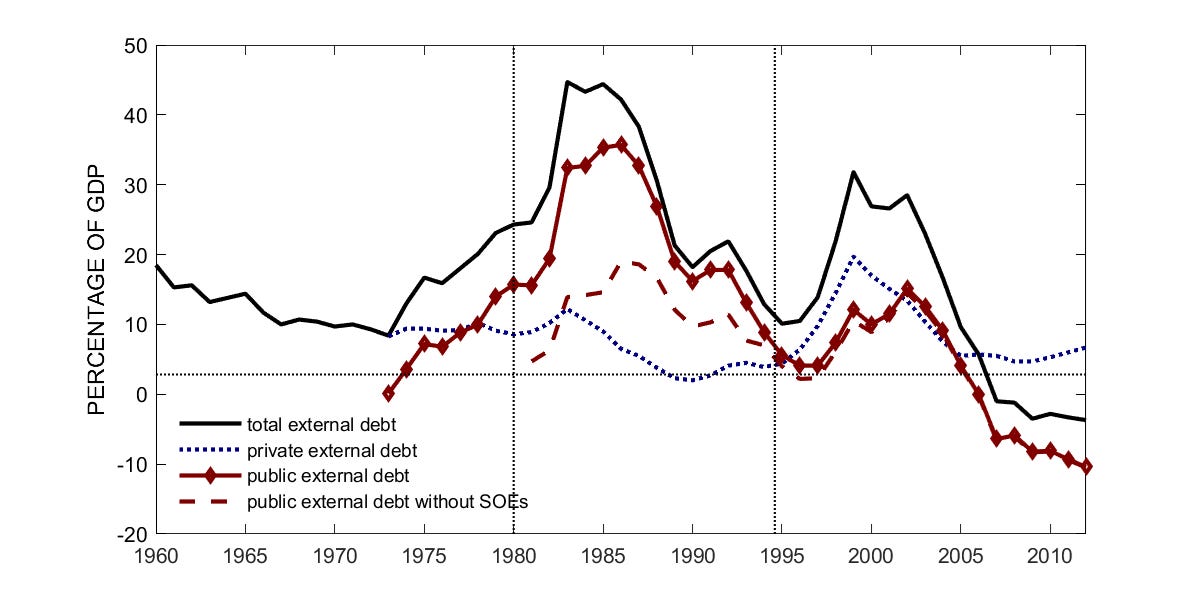

The consequence of adopting the second of these policies6 was dramatic. Growth remained high, but both foreign debt and inflation had large increases by the 1970s (note the log scale for inflation!):

Source for both: Ayres, J., Garcia, M., Guillén, D. A., & Kehoe, P. J. (2019). The monetary and fiscal history of Brazil, 1960-2016 (No. w25421). National Bureau of Economic Research.

This led to the “lost decade” of the 1980s7 with little growth, the external debt crisis of the early 80s, massive increases in inflation peaking with hyperinflation, many failed economic stabilisation plans and, from the mid to late 80s onwards, opening up to imports again8 and decisively ending “classic” attempts at IS, barring some legacy policies like the Zona Franca de Manaus.

There is a debate to be had if the later governments of Lula and Dilma in the 00s did reinstate some IS policies, but overall, one can say that the most striking and important attempt at IS in Brazil lasted for around those 30 years.

A nice little side note is that one positive thing the eventually failure of IS had was that, arguably, one key reason democracy was restored in Brazil was the immense loss in credibility the military had from the economic failures of the 1980s. Particularly coming from as it did after several decades of rapid growth, Brazilians of all stripes were ready to see the end of the dictatorship by the mid 80s and most of the top brass seemed to have realised how badly they had screwed up too… This example of unmatched expectations fits nicely with the general idea that people’s expectations about the future coming from their life experience.

Import Substitution’s Long-term Effects for Brazil

With all that said and done, how well did IS policies serve Brazil in the long-run and what can we learn per the US?

Did it lead to industrialisation in Brazil? Yes, it’s hard to argue it did not. The increase from around 25% to 45% of GDP that we see from the mid 50s to the mid 80s is largely a consequence of this. There’s a big caveat coming, though! Was it exclusively because of tariffs? No, that was very much not the case, Brazil’s policy mix was quite diverse even if tariffs played a major, perhaps the preponderant role, other elements were also very important.

But what sort of industrialisation did Brazil experience? This is a long topic for discussion, so I’m going to do a more superficial discussion. Although not exclusively due to IS, Brazilian industries and companies that resulted from IS policies were not productivity powerhouses, particularly by the end. To wit, at first, the resulting investments IS created did help a lot in increasing productivity of workers, no doubt in part because a lot of decently advanced capital goods were imported into Brazil:

Source: Lara, Cecilia, and Svante Prado. "From boom to gloom: Brazilian labour productivity in manufacturing relative to the United States, 1912–2019." The Economic History Review 76.4 (2023): 1110-1140.

Brazil’s labour productivity reached a high of around 50% of US labour productivity! Brazil really seemed to be ready to “go all the way”… but it didn’t. Noah’s recent post on Trade Deficits helps explain why:

As Noah argues, there are good trade deficits, there are bad trade deficits. Brazil’s deficits in the 60s and 70s did stem imported a lot of useful capital goods… but a lot of it was also just to keep paying for expensive oil. Worse, the very thing that allowed all this to happen was also creating conditions for a lack of continued investment in new capital goods and technology in the 1980s: a lack of competition.

IS creates industries, but these industries know that they aren’t going to face a lot of competition, that’s the point setting up high import tariffs. So, once a company is in, done all the initial high investment and whatnot, there’s not a lot of incentive to keep pace with what other countries are doing, since you’re not trying to export to them, nor facing competition from them inside the protected country. So why bother? Essentially, there’s no market discipline and, worse, it naturally creates vested interests that will want to keep competition out.

This is a key difference between what Latin American countries did with their Industrial Policy and what many argue East Asian countries did with theirs: East Asian countries also imported a lot of capital goods and did industrial policy that was, initially, quite similar to the IS that I’ve described. But, arguably, there was a key focus on exports in East Asian economies that meant companies were always subjected to pressure to improve, invest and get better, something that did not happen much in Brazil.

There’s an excellent graph from the Economist that shows how labour productivity evolved in some key countries over time:

Source: The Economist, https://www.economist.com/the-americas/2014/04/19/the-50-year-snooze

The contrast between Brazil and Korea says everything you need to know, particularly from the inflection point of the 1980s onwards.

To be clear, this is not the only difference between these countries and policies, far from it, I’m very much simplifying and there is some legitimate debate to be had; what I’m presenting is mostly the usual understanding economists have of the Brazilian case. But, to keep this “shorter” post from getting any longer, let’s put that aside for now and try to see what this means for the US.

Could Import Substitution work for the US now?

In short, almost certainly not and even if it could, would the US benefit from it? Let me discuss 3 key points for the first before arguing that the US probably does not want this to succeed.

Firstly, IS in Brazil was done over a period of decades, with significant continuity in policy and consensus among political elite that this was worth pursuing. It was very much not something done over the course of a single government and, indeed, it would not have had much effect if it did. It’s fairly obvious why: it is worth trying to bring manufacturing to a country if high import tariffs will be gone in a few years? In that sense, given the lack of certainty of how long the Trump tariffs will be sustained and the push back it’s receiving, I don’t see how this attempt at industrialisation will work.

Secondly, it almost certainly requires a policy mix that’s not just tariffs. Brazil used several “policy levers” in pursuit of IS, some of which the Trump government is actually disavowing, such the CHIP act’s subsidies. It’s not 100% clear, of course, but based on past experience, we can’t be sure of “success” without more than just tariffs.

Thirdly, the US is not a poor country. Brazil had one key advantage when going through IS in the 1950s: low wages. As many have argued, some manufacturing is still relatively manually intensive work that pays relatively poorly (particularly in the garment industry) and trying to recreate manufacturing in that area alone seems nigh impossible for the US.

Finally, would the US even want the resulting industries? Let’s assume that the US political consensus were to change and tariffs were implemented and other policy tools too. And that this resulted in a big boom in manufacturing. Admittedly, this is rather speculative, but if the US were to follow the “classic” IS formula that Brazil (and other Latin American countries) followed, this would mean that whatever benefits the US would accrue in the short-run would likely come at the expense of creating coddled industries that wouldn’t keep up with the technological frontier.

Obviously the US could try to avoid the pitfalls that Brazil had… but every country that’s ever tried to do Industrial Policy and failed though they had the winning formula too! Industrial Policy can work, but it’s very hard to get right.

To conclude, a coda about my subtitle, Everything Old is New Again. One surprising thing for me with the discussion of the Trump tariffs is how little anyone has discussed about what happened in Latin America with IS, despite the clear if imperfect parallels. The success or lack-thereof of IS in the long-run for Brazil is well understood among Brazilian economists to the point that as a undergrad in the 00s all of the above was already taught as textbook issues; it’s was already an old hat by that point!

Amann, Edmund, Carlos Azzoni, and Werner Baer, eds. The Oxford handbook of the Brazilian economy. Oxford University Press, 2018.

Amann et al.

Again, mostly machines used in factories and the like.

Although the two most famous examples, Petrobras and Vale, predate this era of IS.

The counterfactual for Brazil without IS is hard to do, but the accelaration of growth at the right time is fairly convincing, in my mind.

The dictatorship did also adopt some policies to try to reduce Brazil’s dependence on oil too, to be clear, some of which did eventually pay off, particularly the sugar-cane produced ethanol-for-cars program. But these happened many years later.

Which arguably lasted until the mid 1990s and the Plano Real stabilisation plan.

Relatively speaking. Brazil’s import tariffs remain some of the highest in the world!

Excellent article, Pedro! I am glad to see you quoting from the work of Werner Baer, one of the best scholars of Brazil's industrial policy and ISI, who was my mentor and master's thesis advisor at the University of Illinois, and Edmund Amann, a friend and colleague at Johns Hopkins SAIS Europe.